I’ve told my friends many times that the only time I’ve had a religious/mystical experience was not when attending any religious service or reading any scripture, but when listening to the music of Bob Marley. Nothing embodies the religious feeling I get from his music more than the song “Natural Mystic” which opens with the following verse:

If you listen carefully now you will hear”

From this verse, we understand that the mystical is something to be felt, as opposed to being understood. You need to listen, to feel the mystic – whatever that is – you can’t look for it with a telescope or deduce it from other facts. This brings us to a statement by one of my favorite philosophers Bertrand Russell, who in his essay “Logic and Mysticism” states:

“Mysticism is, in essence, little more than a certain intensity and depth of feeling in regard to what is believed about the universe;”

In “Logic and Mysticism” Russell looks at whether the statements of mystics throughout history carry some truth in them, and whether mysticism is a valid way of gaining knowledge about the world. As the term mysticism itself is ambiguous, and extremely diverse and disparate schools of thought are described as being mystical (e.g. Sufism, Kabbalah, Buddhism, New Age thought, etc…), he first provides what he considers to be four central beliefs common to most mystical schools of thought, presented as four questions:

“Four questions thus arise in considering the truth or falsehood of mysticism, namely:

- Are there two ways of knowing, which may be called respectively reason and intuition? And if so, is either to be preferred to the other?

- Is all plurality and division illusory?

- Is time unreal?

- What kind of reality belongs to good and evil?”

It is this first question which I will address in this post:

- Are there two ways of knowing, which may be called respectively reason and intuition? And if so, is either to be preferred to the other?

Russel then goes on to provide details of how mystics see intuition as a form of acquiring knowledge.

“There is, first, the belief in insight as against discursive analytic knowledge: the belief in a way of wisdom, sudden, penetrating, coercive, which is contrasted with the slow and fallible study of outward appearance by a science relying wholly upon the senses.”

“The mystic insight begins with the sense of a mystery unveiled, of a hidden wisdom now suddenly become certain beyond the possibility of a doubt. The sense of certainty and revelation comes earlier than any definite belief. The definite beliefs at which mystics arrive are the result of reflection upon the inarticulate experience gained in the moment of insight.”

“The first and most direct outcome of the moment of illumination is belief in the possibility of a way of knowledge which may be called revelation or insight or intuition, as contrasted with sense, reason, and analysis, which are regarded as blind guides leading to the morass of illusion.”

Russell contrasts the above described mystical way of obtaining knowledge with what he seems to interchangeably describe as reason, logic, science and intellect. From the text, it is clear that he is talking about the combination of logic and empiricism as the true method of acquiring knowledge, and therefore holding a position which I would describe as proto-logical positivism (although unlike the logical positivists he isn’t as dismissive of metaphysics). This is fitting since he is in a sense the intellectual grandparent of the Vienna circle (Russell’s protege Wittgenstein inspired the Vienna Circle’s central ideas with his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus.).

Russell then develops the idea that what the mystics are talking about when they speak of intuition or insight is in fact instinct, and he compares instinct versus reason as a means of obtaining true facts about the world. He concludes that instinct, while useful for some practical day to day tasks (as a skill acquired by evolution), cannot lead a person to a greater theoretical understanding of the world. Towards the end of the first section of his essay he states: “It is not in philosophy, therefore, that we can hope to see intuition at its best. On the contrary, since the true objects of philosophy, and the habit of thought demanded for their apprehension, are strange, unusual, and remote, it is here, more almost than anywhere else, that intellect proves superior to intuition, and that quick unanalyzed convictions are least deserving of uncritical acceptance.”

It is my opinion that Russell does injustice to the mystics in his assessment of the mystical way of knowledge. The mystics are indeed pointing to a different way of acquiring knowledge other than logical empiricism, but it is not in the form of intuition which Russell describes. Instead I would posit that there is indeed a second way besides science/reason/logic of acquiring knowledge, and that is through practice and repetition, and that is what the mystics were talking about, even if they occasionally describe it in otherworldly or seemingly paradoxical ways.

Let me explain how acquiring knowledge through repetition and practice is different from the scientific way of acquiring knowledge. I need to point out two things: First, I realize the pretentiousness of a self declared “philosophy wannabe” going up against Russell – one the greatest minds of the twentieth century – and trying to prove him wrong. Readers, just humor me on this one. Second, my explanation here is not rigorous in any way. It is anecdotal and based mostly on my own experience. I still think that many will agree with my point of view.

Here’s my argument in brief: Some knowledge about the world can only be acquired via practice and repetition. This knowledge is theoretical knowledge in the sense that Russell described above, yet it still has to be practiced and acquired like a skill, and cannot be arrived at by reason or science alone. This is the intuition that mystics were talking about, not intuition as it was described by Russell.

First let’s establish a fact that everyone agrees on: Skill on a musical instrument or skill in a particular sport cannot be arrived at by theoretically knowing how to play that instrument or sport, or even after someone has seen practical demonstrations of how to do so. A person has to practice for hours, days, or years (some claim 10 000 hours) to achieve expertise in such an activity. In music at least, there are many people who know how to play a difficult piece, without being able to play it. One would argue that in the case of musical or athletic abilities, these don’t constitute knowledge in the epistemological sense that Russell was talking about in “Logic and Mysticism,” since they are practical, physical abilities. And yet here we already notice that in every day language, people tend to use “knowing how to” and “being able to” interchangeably, so intuitively (pun intended) there seems be some relation between practical ability and epistemic knowledge.

Now I will give a second case were the difference between practical skill and epistemic knowledge is not as obvious: Learning languages. When learning human languages, or even better, when learning programming languages, it is clear that simple theoretical knowledge of how to speak or program in a language does not constitute “knowledge” of that language. Lots of practice and experience is necessary before someone can legitimately claim to know Japanese or Java programming. Yet at the same time speaking Japanese or programming in Java are closer to theoretical knowledge than playing an instrument or a sport, in the sense that they are mental abilities, not physical abilities.

The third case I will present is more contentious, but I believe that the same thing applies here as well. A few years back when I was in grad school I attended a study session on Hilbert Spaces. The book we were studying was Introduction to Hilbert Space, by Paul Halmos. The professor facilitating the lecture warned us that the book was very well written and thus could give us a false sense of understanding, given how clearly the subject was presented. He insisted that we wouldn’t truly understand Hilbert spaces until we had worked through several problems and examples ourselves, and he was right. I felt the same way when dealing with some of the more advanced optimization methods or pattern recognition algorithms I came across during my graduate studies. Having a perfect understanding of the definition of a concept wasn’t enough to truly “get it”; once must work through examples and see the concept in use to get a gut feel for it. To bring us back to the Bob Marley verse, one had to be able to feel the concept, and not just understand it. Most undergrads dealing for the first time with Fourrier or Laplace transforms must have had similar experiences, and this probably applies to most hard sciences, not just math. The point I am trying to make here is that, even in a discipline as theoretical as mathematics, and hence part of true knowledge (in the sense that Russell uses the word), concepts require practice and repetition to be properly acquired. Logic on its own does not suffice.

Now for the final piece of my argument: What the mystics are teaching is that some moral and ethical truths (typically bundled under the label spirituality) can only be acquired through practice and repetition. Many schools of mysticism would have included various debatable metaphysical facts (knowledge of God, the unity of existence, etc.) among those that should be learned through practice as well. But I believe that it is fair to say that they also include concrete ethical facts about the world that even a hardened positivist such as Russell would concede were real. Things such as compassion, tolerance, love, the impermanent nature of things, detachment from material possessions, etc., these are like skills that someone has to train him/herself in, the type of knowledge that can only be acquired by practice and repetition and not knowledge that could be acquired through logic and empiricism alone. Yet they also fall in the category of theoretical knowledge as Russell described above.

Hence mystical schools always speak of paths, tariqas and practices. The Sufis have their dhikr and their chanting. Buddhists have meditation and mantras. Hindus have their yoga practices, and I am sure that other schools of mysticism have practice and repetition based approaches to knowledge as well. It is no coincidence that many schools of martial arts are associated with Eastern mystical traditions, as the concept of practice and training is central to both.

But what then of Russell’s identification of mystical knowledge with instinct? He is in a sense correct. What he misses here is that instinct can be acquired and not just inherited through genetics. Someone can gain enough intuition on a question until it becomes the same as instinct. People often speak of something becoming “second nature”. To go back to the math and hard sciences example I mentioned earlier, people speak about getting an “intuitive feel” for a problem or a topic. But mastery of a topic is nothing but knowledge of that topic becoming like an instinct. All though many have reported having “Aha!” moments when searching for solutions to science and engineering problems, that are sudden in the way Russell described above, these have only come after long periods of thinking about the topic, and not just out of the blue. Here we can see the value of meditation, which is a central ingredient in just about every mystical school of thought. One could argue that meditation is nothing but mental exercise, the neurons’ equivalent of weight lifting and endurance running. A runner must run to be able to complete a marathon and a computer programmer practice to become a competent developer. And so it is with meditation, which is how one learns to be more proficient at tolerance or patience.

To summarize: Russell states in “Mysticism and Logic” that mysticism provides an alternative epistemological method to science, which he deems to be based on instinct and intuition as a way of arriving at the truth. After discussing the differences between the two (scientific vs mystical knowledge), Russell deems the mystical method to be ultimately false and misleading. I argue that mysticism does indeed provide an alternative epistemological method to science, but that is not what Russell describes it to be. Instead, it is the method of acquiring knowledge through practice and repetition, and that it is complementary to the scientific method, not opposed to it. I have shown through examples some types of theoretical knowledge that can only be acquired through practice. repetition and meditation. And that these are the types of knowledge that mystics are talking about when they speak of intuition.

Russell might be correct in his assessment of the other three questions regarding mystical schools of thought, but I believe he missed the mark when it comes to assessing the mystical way of acquiring knowledge.

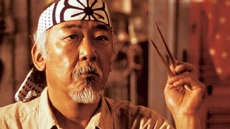

Ultimately, this idea reminds me of Mr Miyagi, and the way he forced Daniel-San to manually clean all of his cars and walls as the best way to learn Karate, until his guard and strike reflexes become intuitive, like a second instinct. Maybe that is how we can feel the Natural Mystic, by repeating things ad sapientiam.

Categories: Philosophy, Science

long hiatus?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah – Work. I have something brewing though, will post soon.

LikeLike